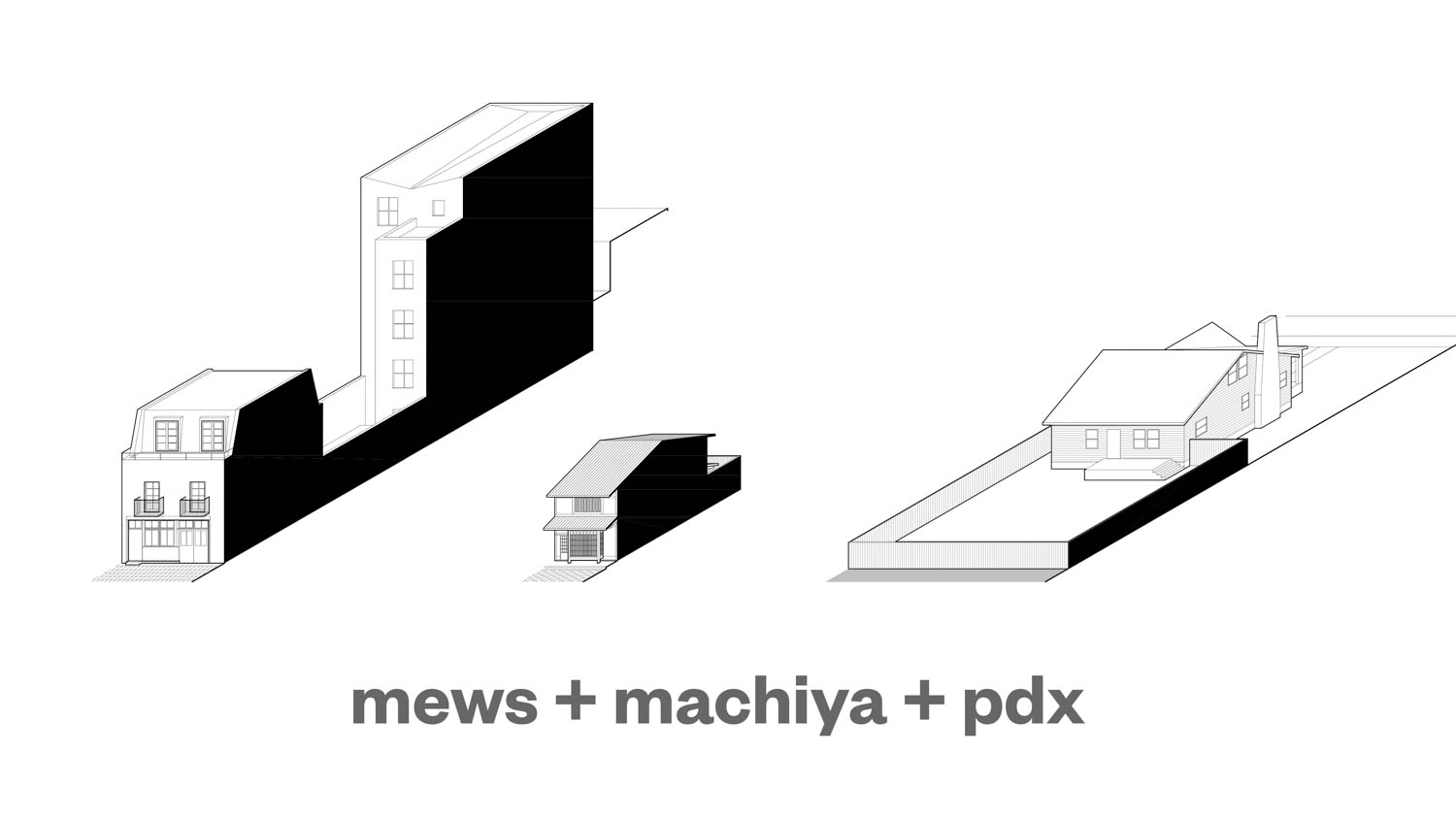

Design ideas for new infill housing on Portland’s alleyways / Jonathan Bolch – Part 3 Mews + Machiya + PDX

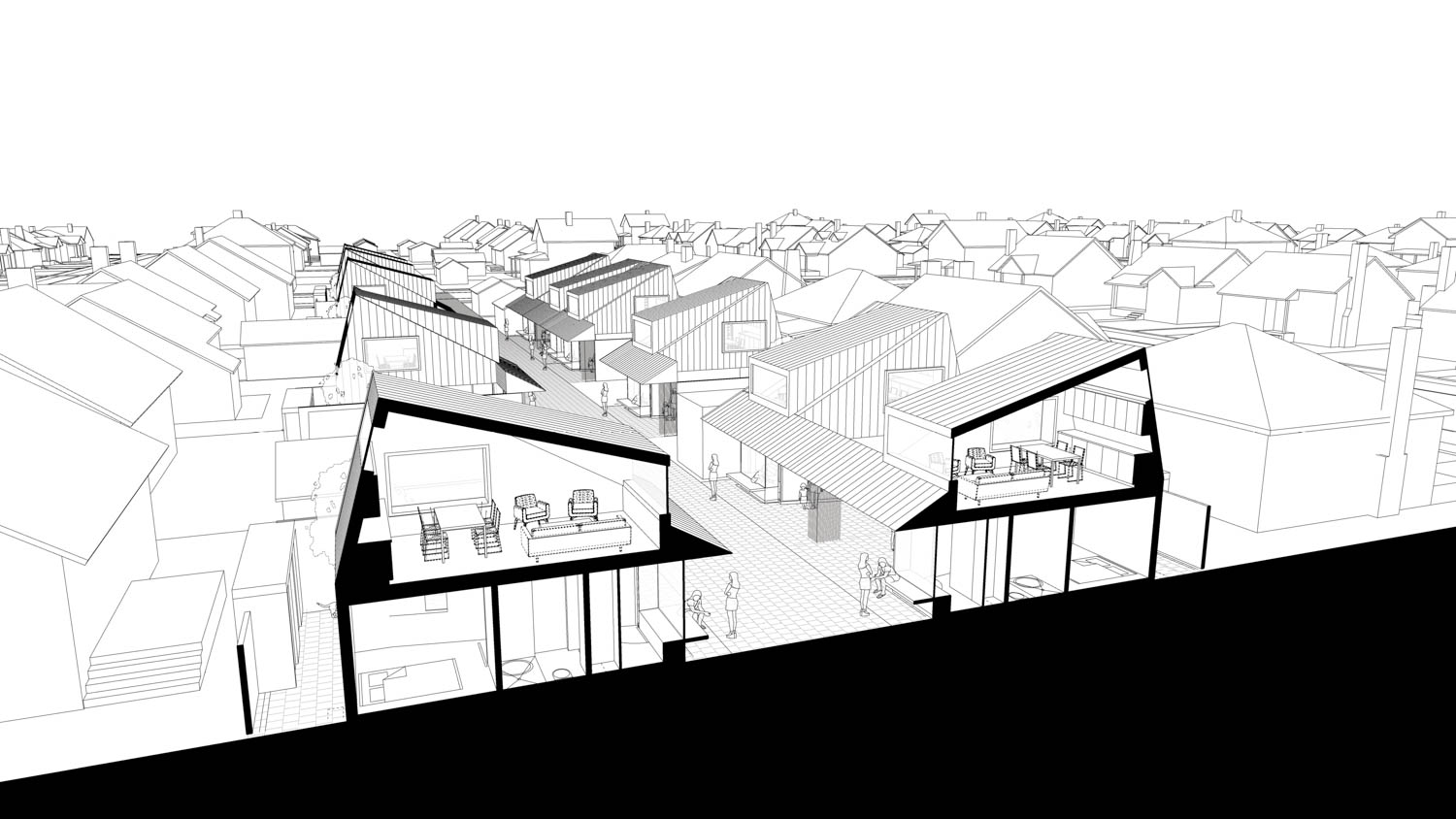

Having explored Portland’s rich urban fabric and gleaned insights from global precedents like Kyoto’s machiya and London’s mews, Part 3 turns to concrete design ideas for transforming the city’s underutilized alleyways. This section tackles the unique challenges of infill housing on narrow blocks—from coordinating disparate property owners to ensuring “eyes on the street” for enhanced safety—by proposing innovative, modular prototypes that harmonize individual needs with a collective, pedestrian-friendly community vision.

for more laneway / or narrow block homes

What are the biggest challenges in designing infill housing for alleys, and how can these challenges be addressed through innovative design and planning?

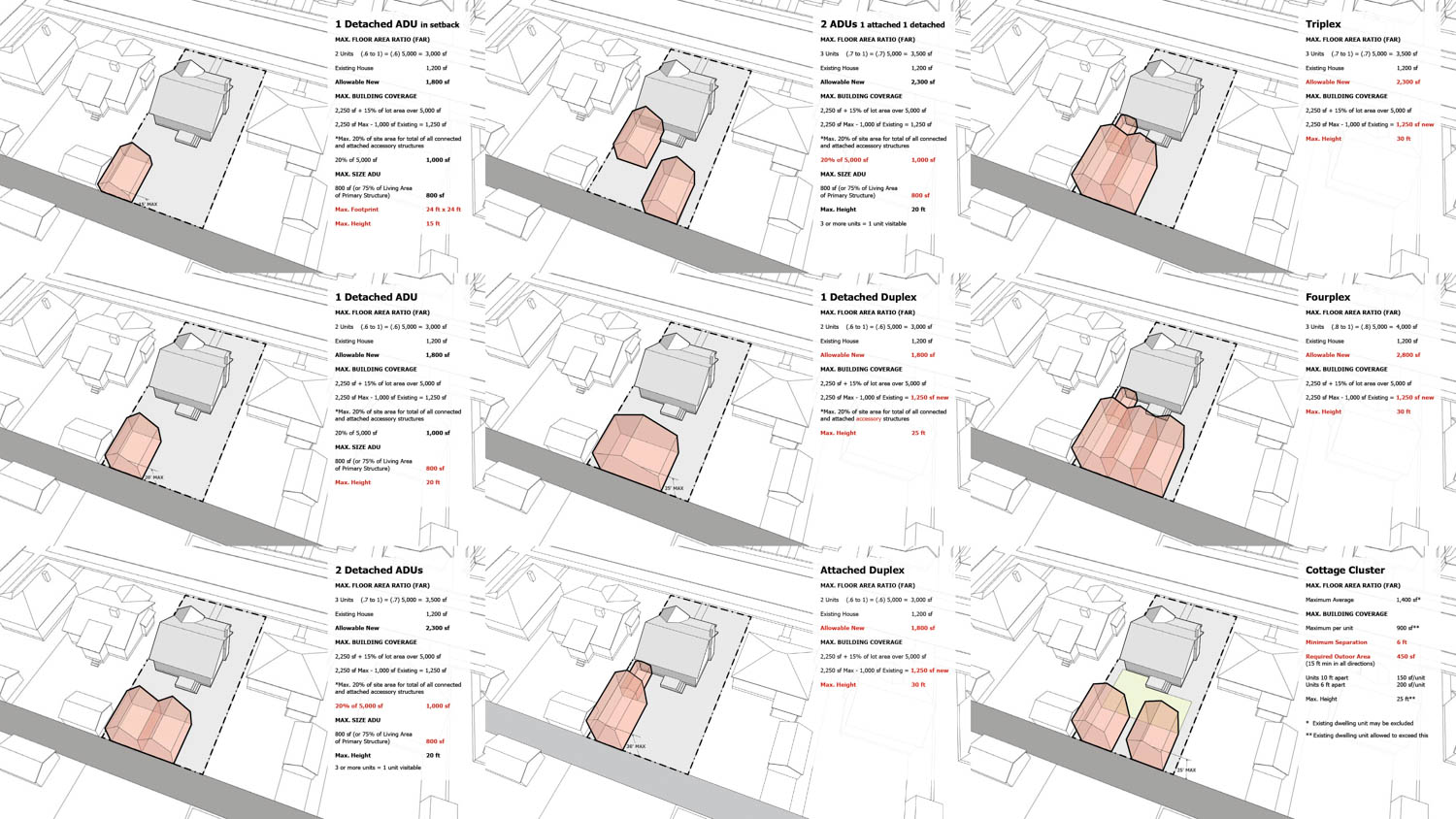

Even with the wonderful opportunities provided by the new zoning codes, there are still several challenges in designing infill housing for alleys in Portland. One is residential alley blocks typically are formed by a collection of individually owned lots. To realize the goal of transforming our alleys into pedestrian-oriented community spaces, multiple homeowners on the same block would need to develop their properties toward this common vision.

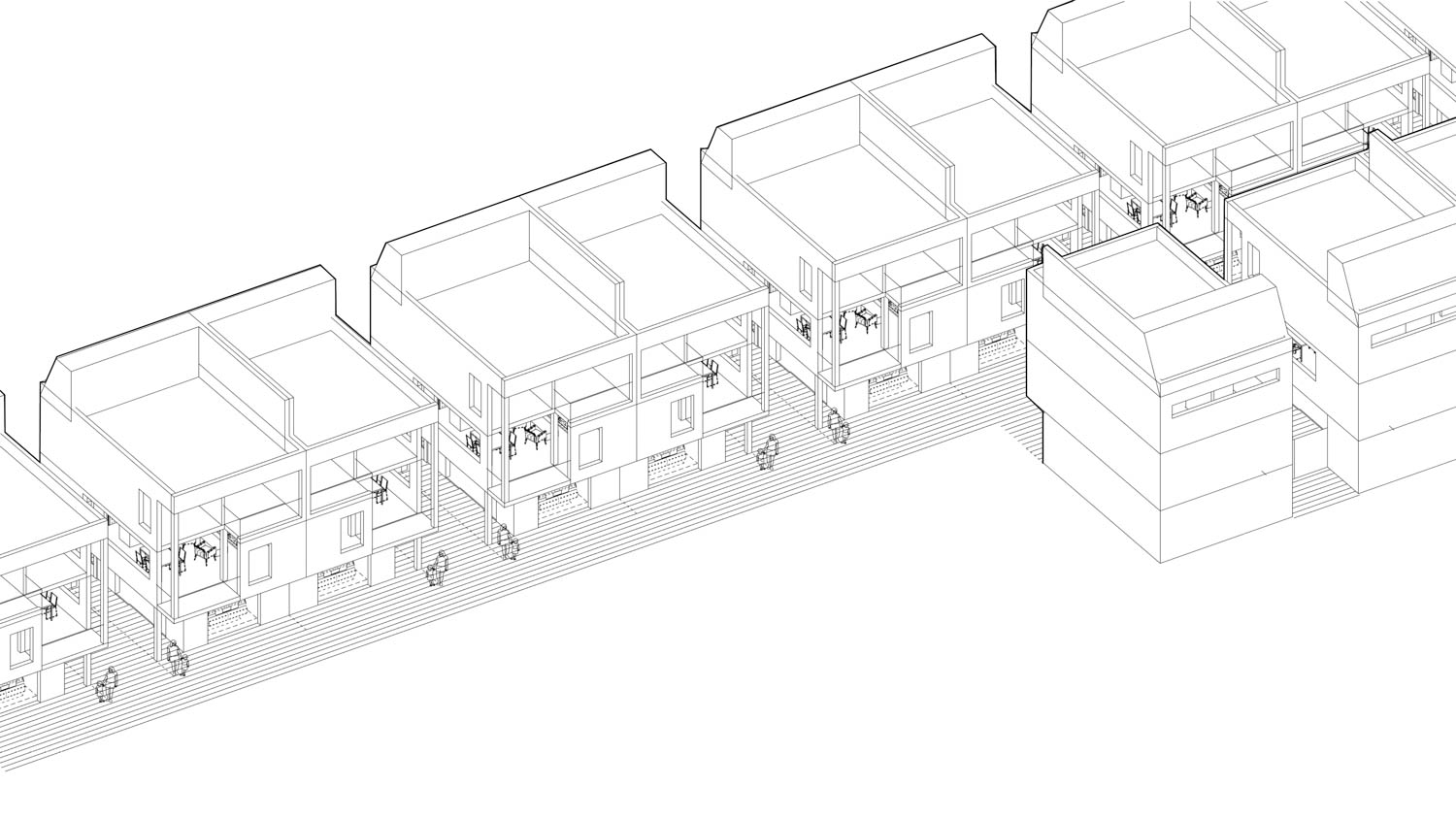

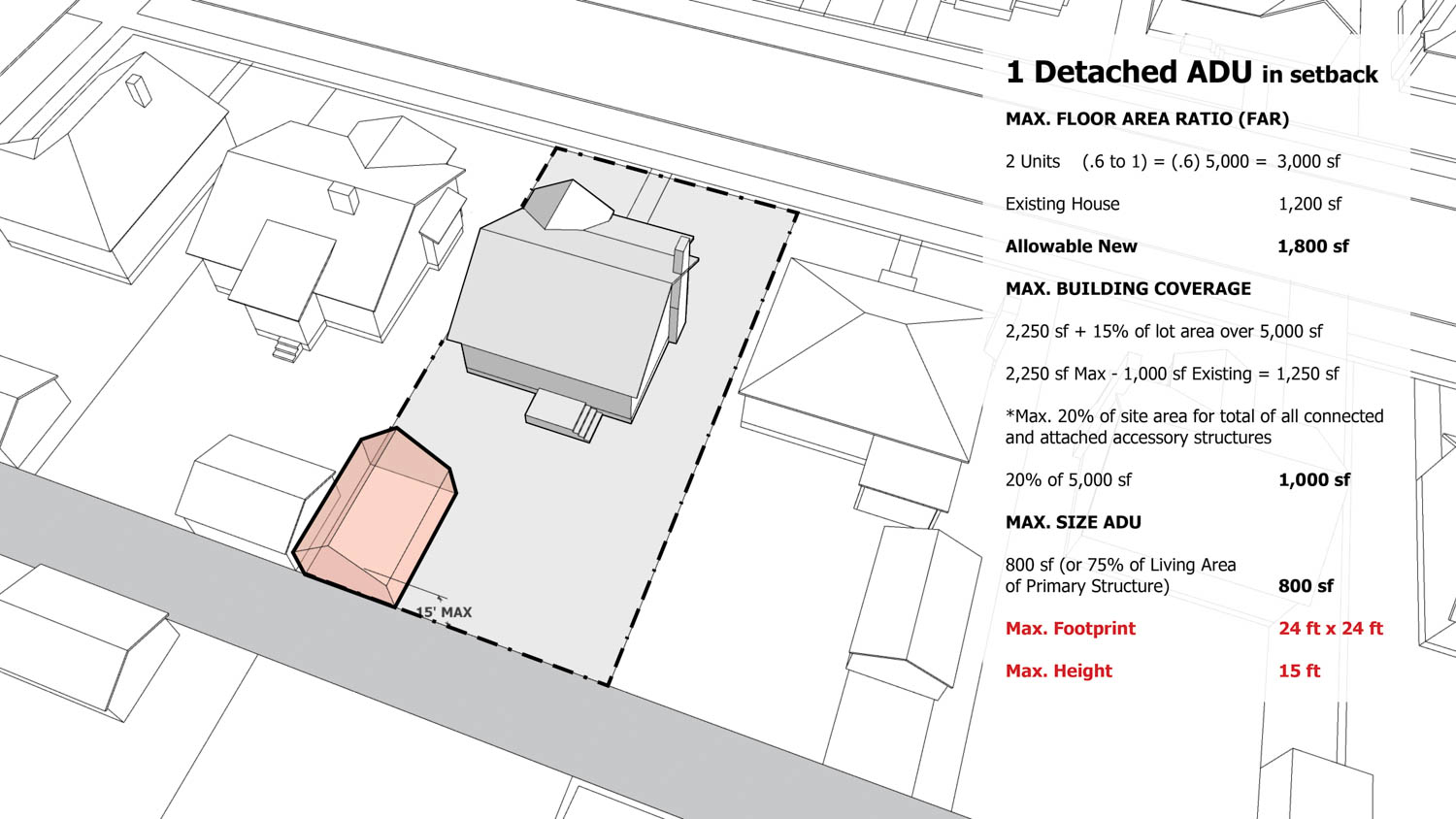

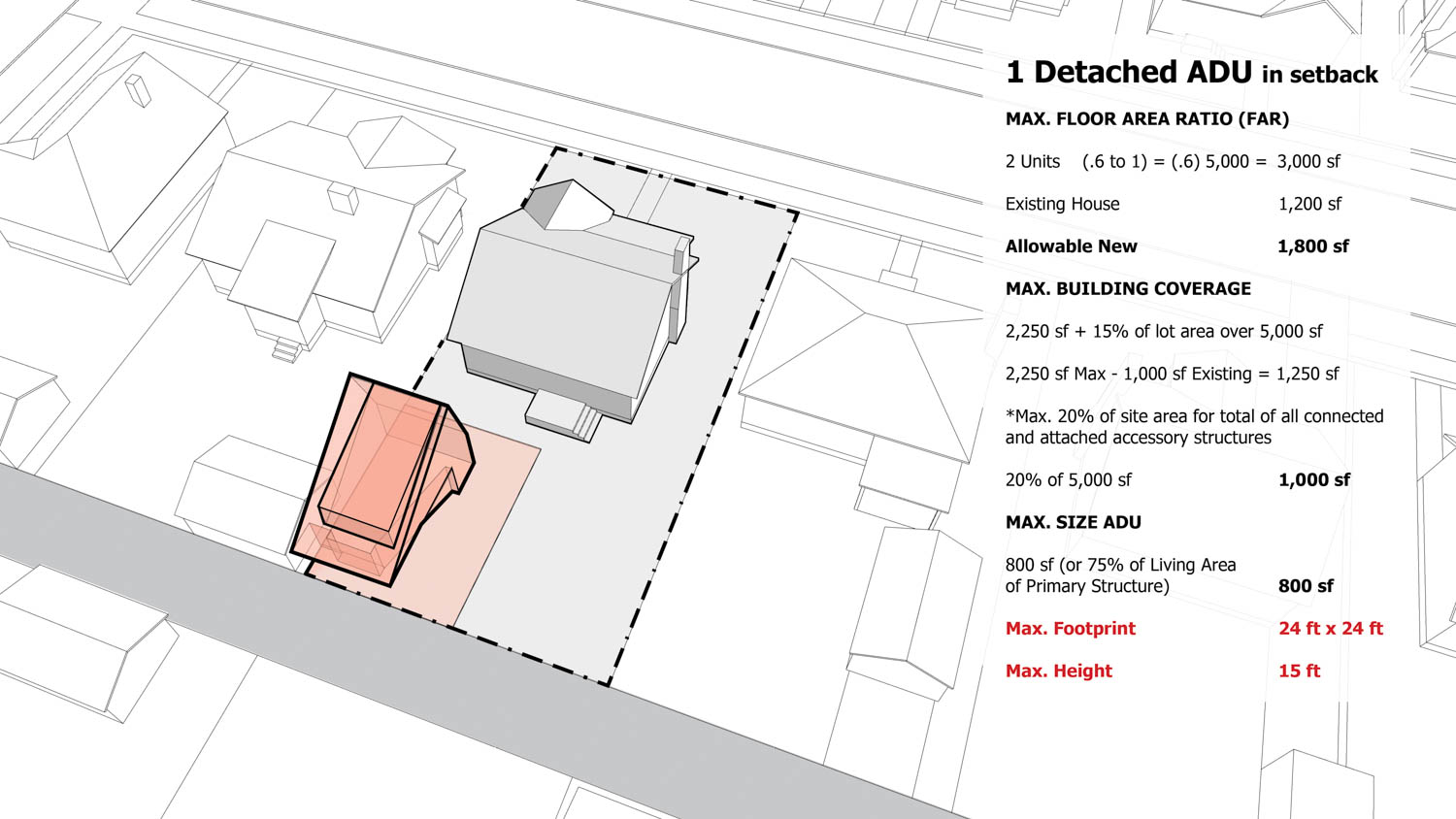

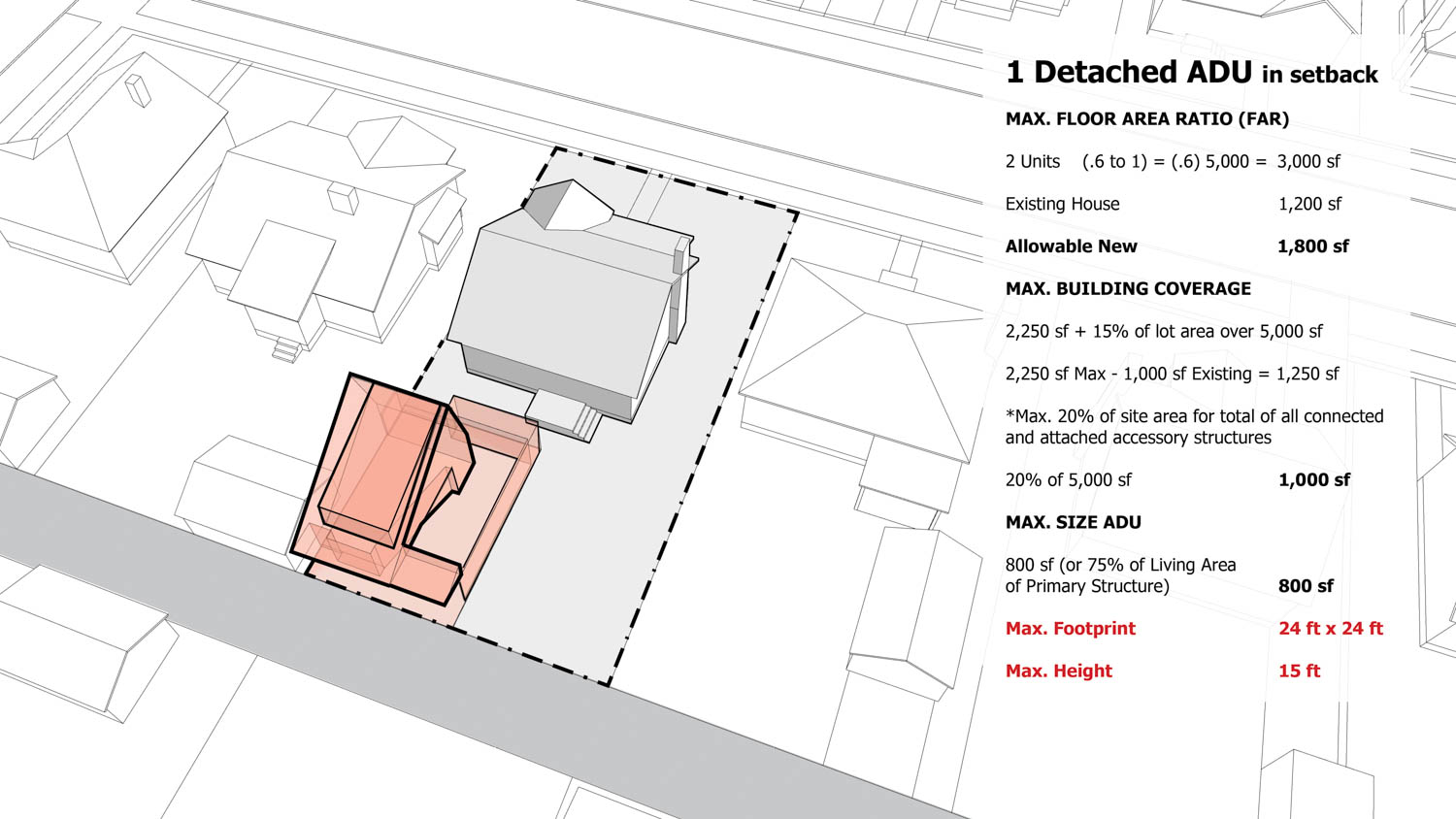

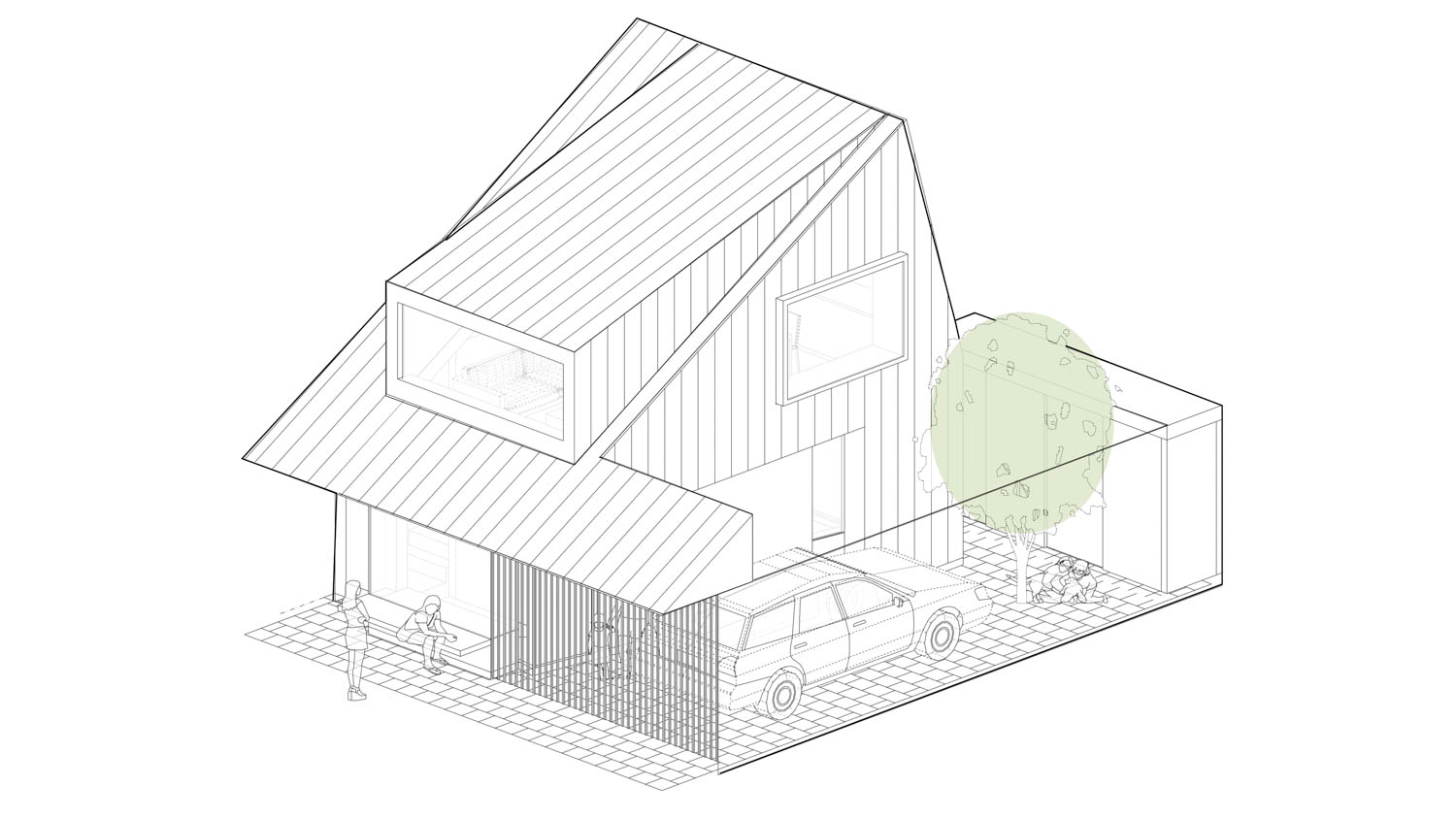

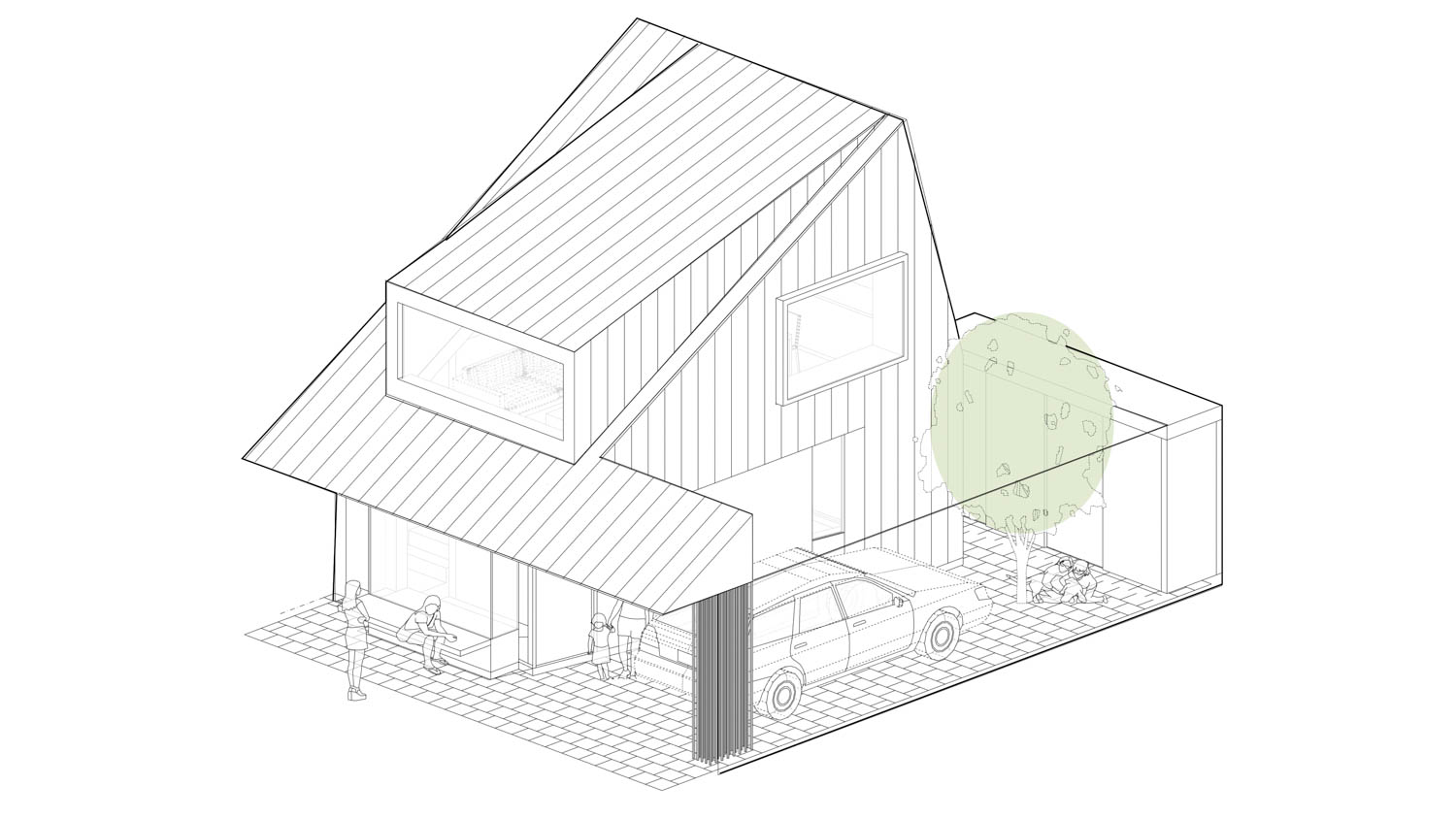

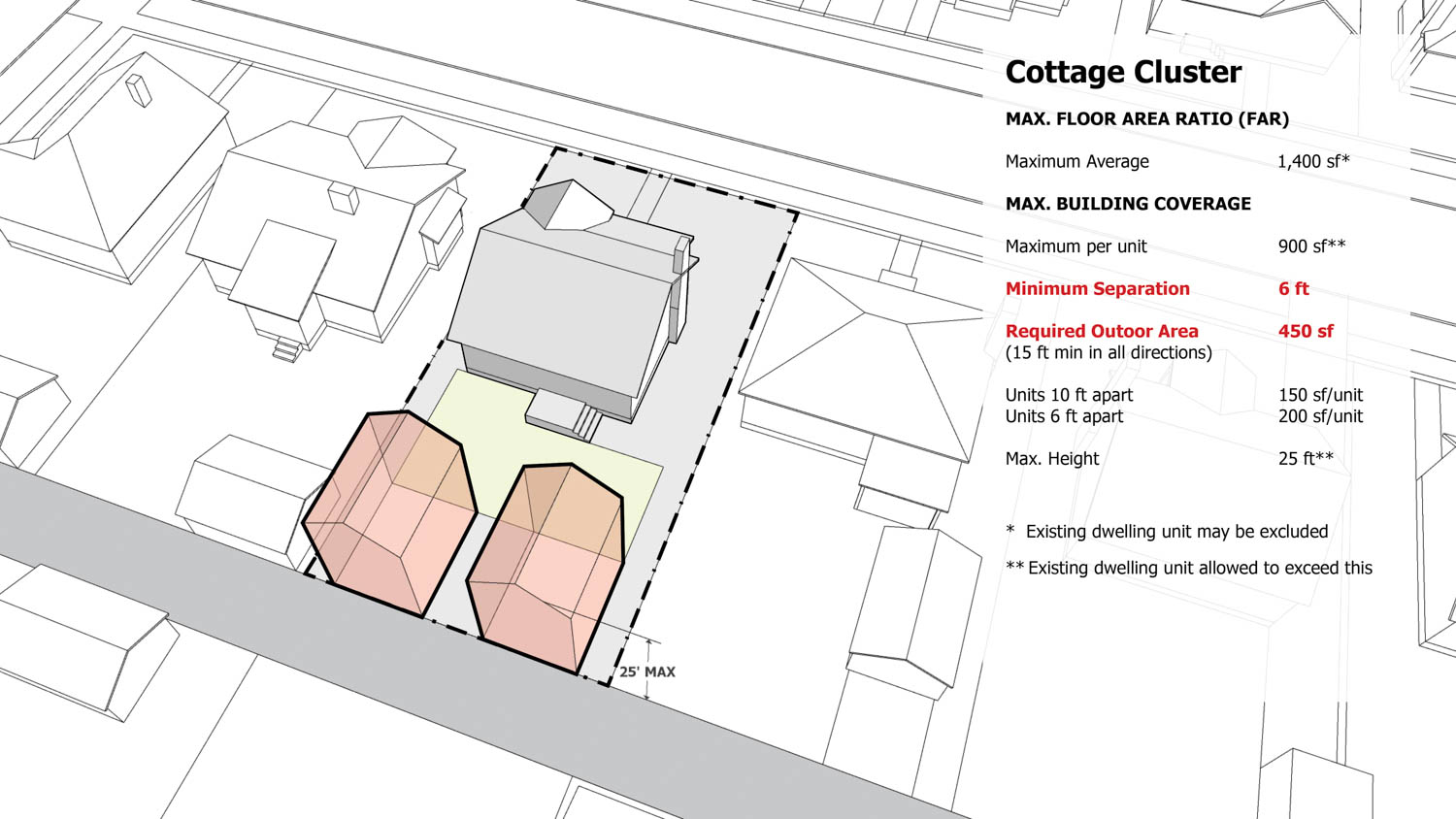

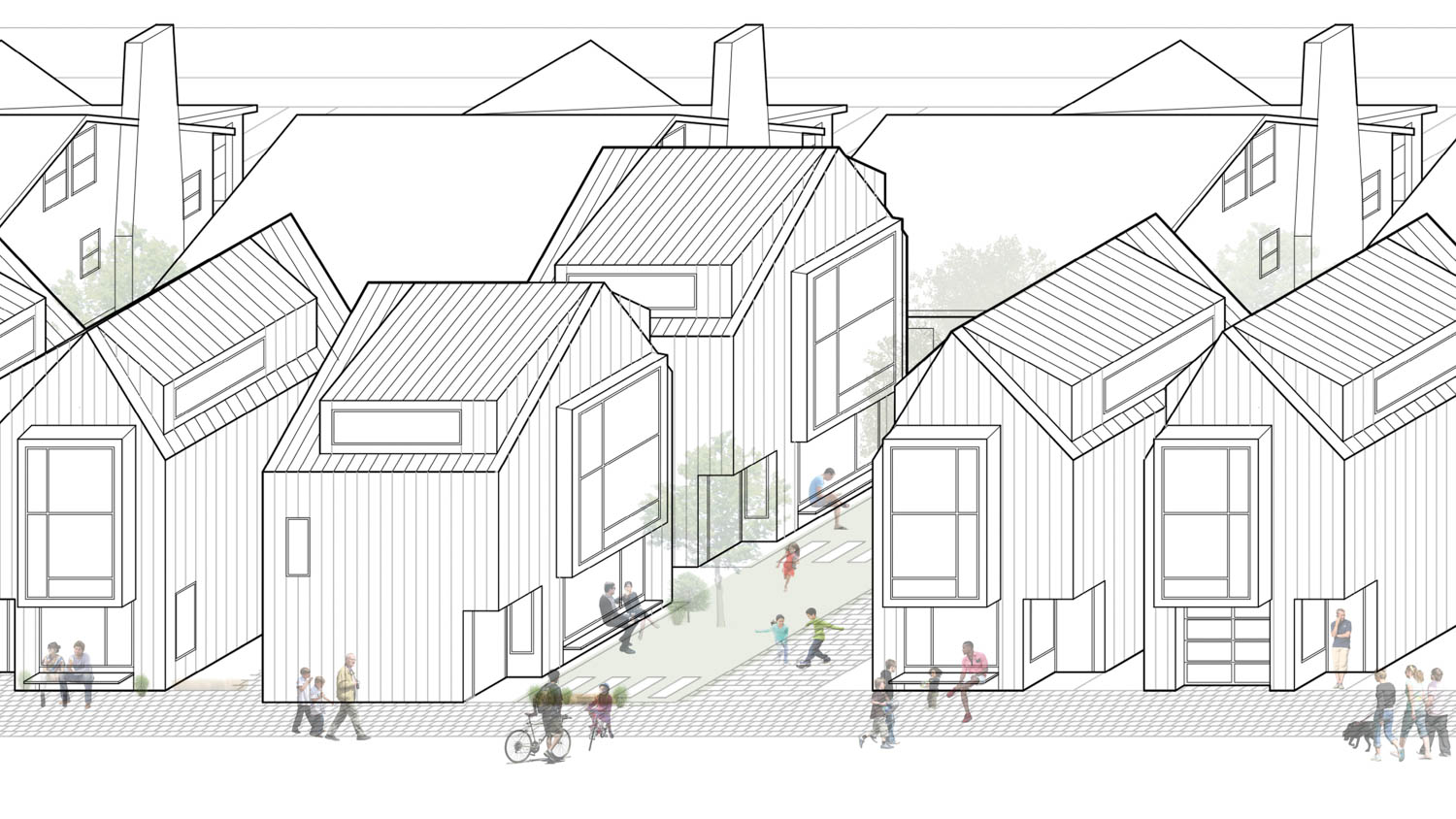

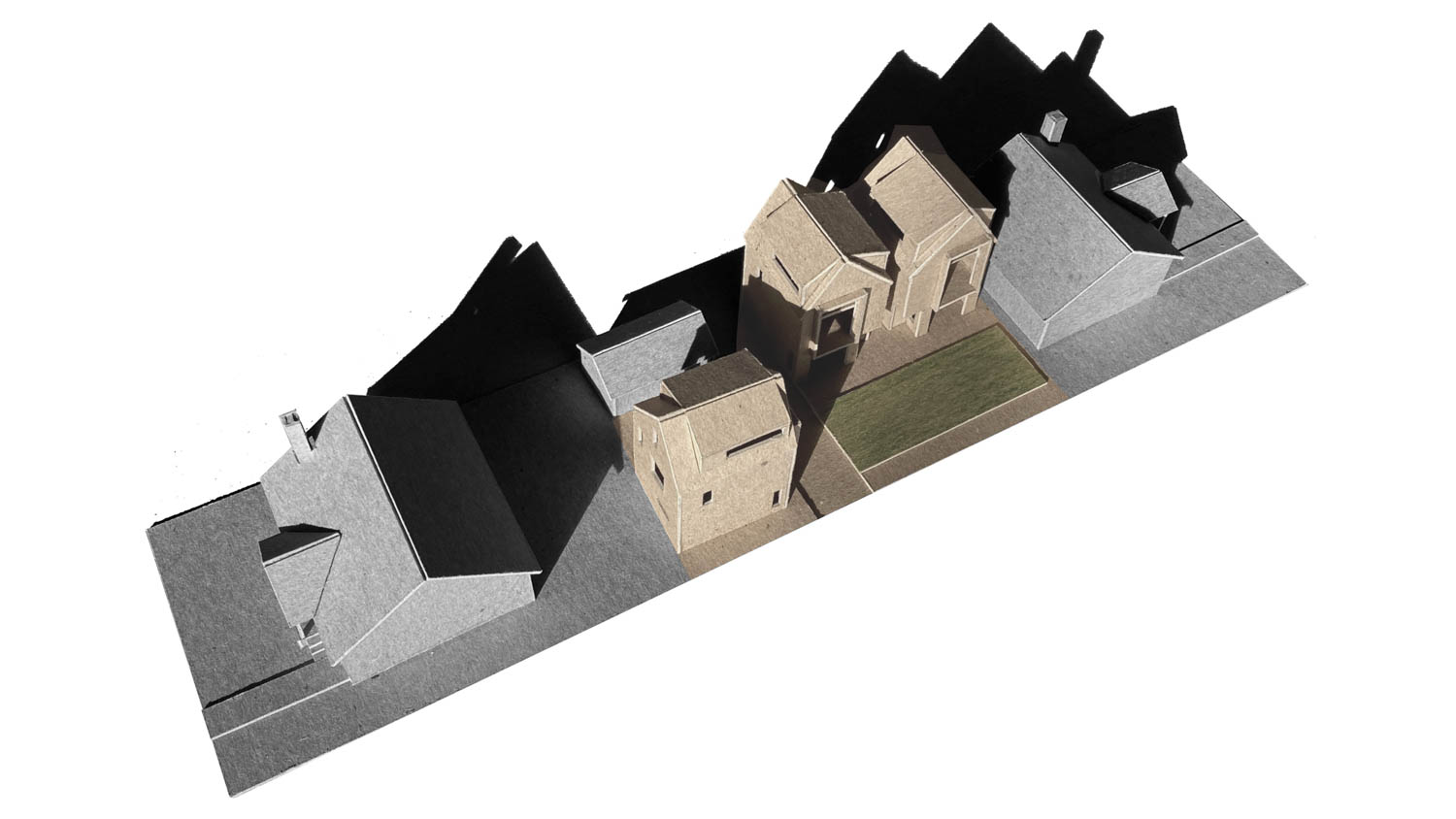

One idea guiding my infill studies is to create designs that work individually as a small, self-contained world that can also aggregate to support community space and interaction. I have developed several prototypes that fit in a modular portion of a typical 50’ wide by 100’ deep Portland lot so that a homeowner could potentially sell off a piece of their property so that the alley-facing frontage could be developed separately. For example, I have developed multiple concepts that fit on a quarter lot (50’ wide x 25’ deep). That way, in concept, homeowners could potentially sell the alley-facing portion of their lots to another entity interested in developing new homes embracing the alleyway.

However, even though the codes here were revised to make it easier to subdivide lots through “Middle Housing Land Divisions” to provide more opportunities for ownership, they are currently written such that property can only be subdivided once a building permit is in hand for the new building. Thus, a homeowner could not currently divide their lot to sell of an alley-facing portion without first developing (and paying for) the design and permitting of the new structure on the lot to be sold. I am hopeful that through the use of third party developers, who help act as a financial and organizational bridge, homeowners can have multiple options for developing and subdividing their properties.

Ideally, individual homeowners could densify and develop their lots to meet their individual needs—multi-generational living, work-from-home spaces, co-housing scenarios, income opportunities—while keeping in mind the collective opportunity to create a shared community resource by engaging the alley.

Costs are another challenge. My hope is to encourage incremental infill in backyards that takes advantage of specific existing opportunities and preserves the existing houses. But this involves customization of each design for its unique context, when combined with the inefficiencies of small structures, increases costs per square foot.

To help mitigate this, I am working on simple, compact design prototypes that fit in a variety of typical backyard contexts and minimize site customization. Also, in Portland there are alternative forms of financing available to assist lower income homebuyers that create ongoing affordability.

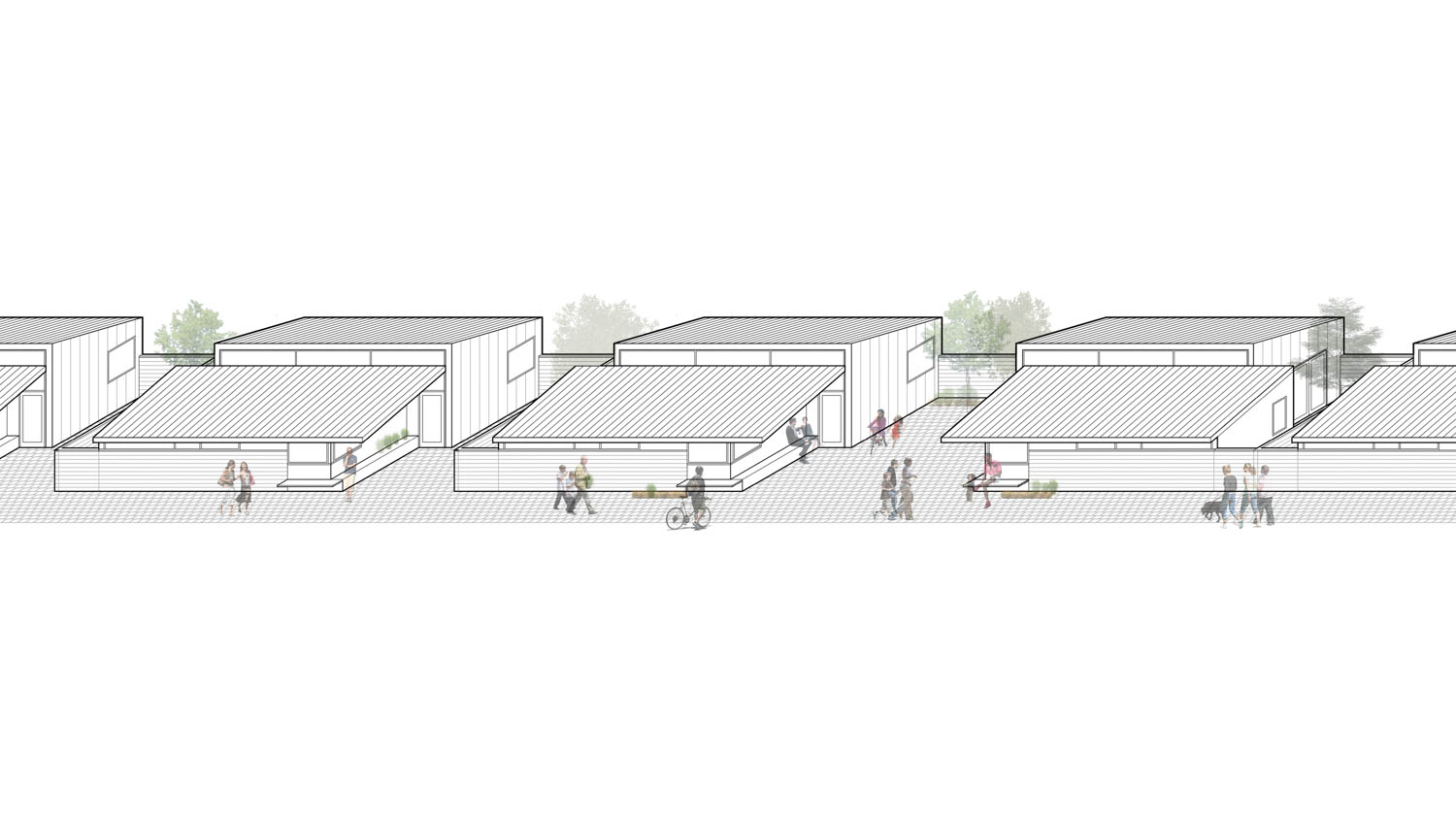

How can the concept of ‘eyes on the street’ be leveraged in alley-facing housing to create safer and more engaging community spaces, while maintaining the charm and character of the alleyways?

I am fascinated by the challenge of compact individual unit design but even more interested in how they can work together and form successful spaces in between. The current condition in Portland is the opposite of “eyes on the street.” With their blank walls of fences, there are no eyes on the alleys. So much so that I have heard from homeowners on lots abutting alleys that sometimes people will even drive to alleys and surreptitiously dump their trash there.

A guiding theme of my research is encouraging “front doors on back alleys” and reversing the current condition. The small scale of alleys can be charming, but it also creates a challenge for privacy, as eyes out can equal eyes in.

I think Kyoto’s machiya are terrific precedent to address this. Through their clever use of lattices, translucent screens, and subtle demarcations of boundary through paving and overhangs, they create layers of privacy for their interior spaces, maintaining connections out but limiting views in.

Additionally, their traditional use as live-work spaces with the shop space facing the alley is inspiring for Portland, with its ethos of makerspaces and independent creative endeavors. Whenever possible, I think the ground level spaces of new homes facing the alley should be open and flexible, potentially used as a small workshop, retail space, or home office. This way the new homes can truly embrace and enliven the public space of the alley.

I think fences are also a critical element to reconceive. Instead of mute walls marking boundaries, they should be seen as an extension of the architecture and as two-sided opportunities to define and connect exterior spaces. They could slide open to connect yard to alley when desired, they could vary in height and opacity strategically, they provide opportunities for display and vertical gardens. One joy of the compact, pedestrian scale of alleys is that every homeowner along them has the opportunity to have a significant impact on their character and personality, block by block.

Previous Article