Q&A with Woofter Bolch Architecture: Rethinking Backyard Living with the Birch ADU

The Birch ADU is a compact, sustainable housing prototype designed by Woofter Bolch Architecture, awarded the Grand Prize in the ADU category of the 2021 Salt Lake City Empowered Living Design Competition. Tailored for alley-access lots but adaptable to any urban site, the design reimagines how we use backyard spaces — balancing affordability, flexibility, and community connection. In this Q&A, the architects share their thinking behind the project, and how small-scale design can play a big role in shaping cities.

for more laneway / or narrow block homes

1. What inspired the design of the Birch ADU, and why focus on alley-access lots?

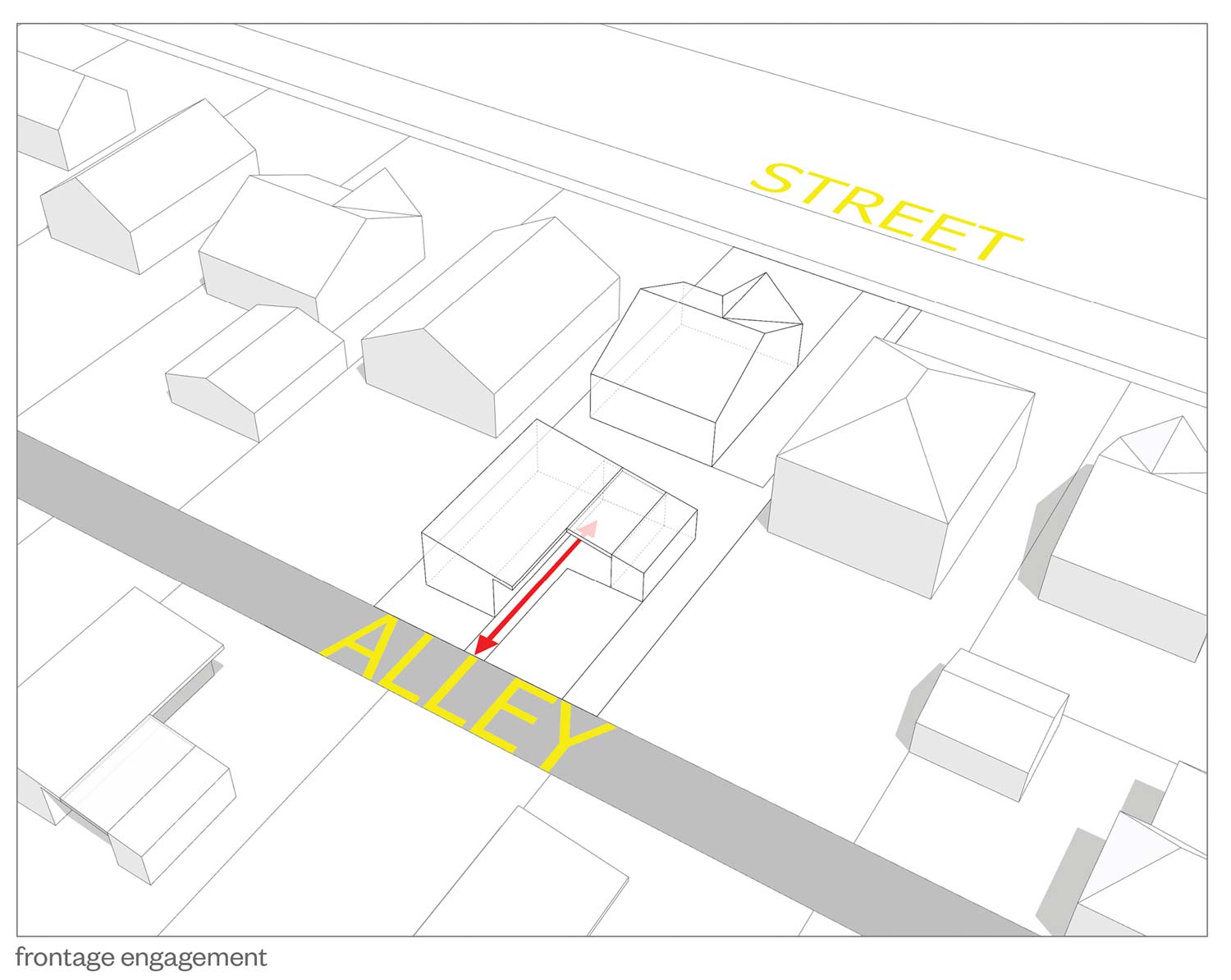

Woofter Bolch Architecture: We were inspired by the untapped potential of Salt Lake City’s residential alleys — these spaces offer a unique opportunity to introduce density without disrupting existing neighborhood character. The Birch ADU is designed to work within those overlooked conditions. By using the rear lot and maintaining the street-facing home, it becomes an affordable, respectful form of infill housing.

2. What makes the Birch ADU different from a typical backyard cottage or granny flat?

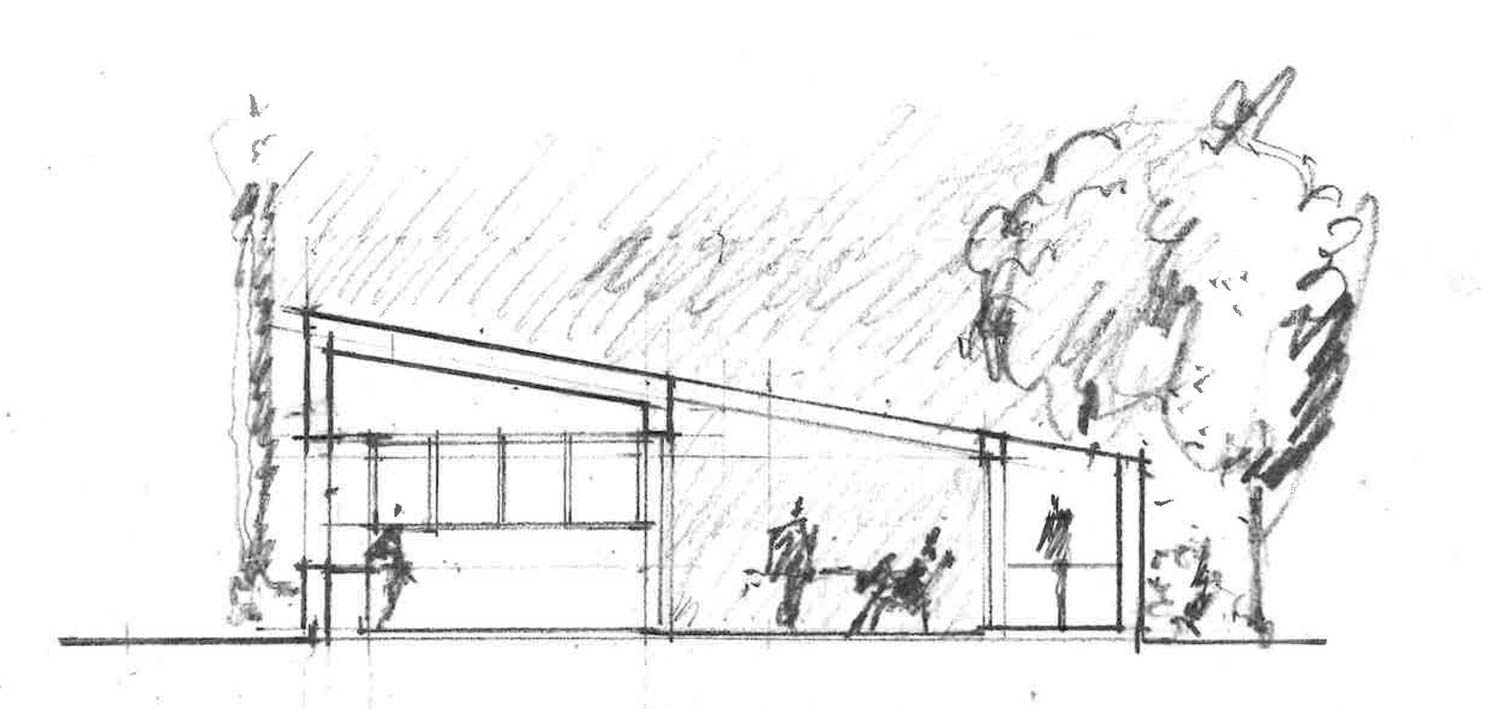

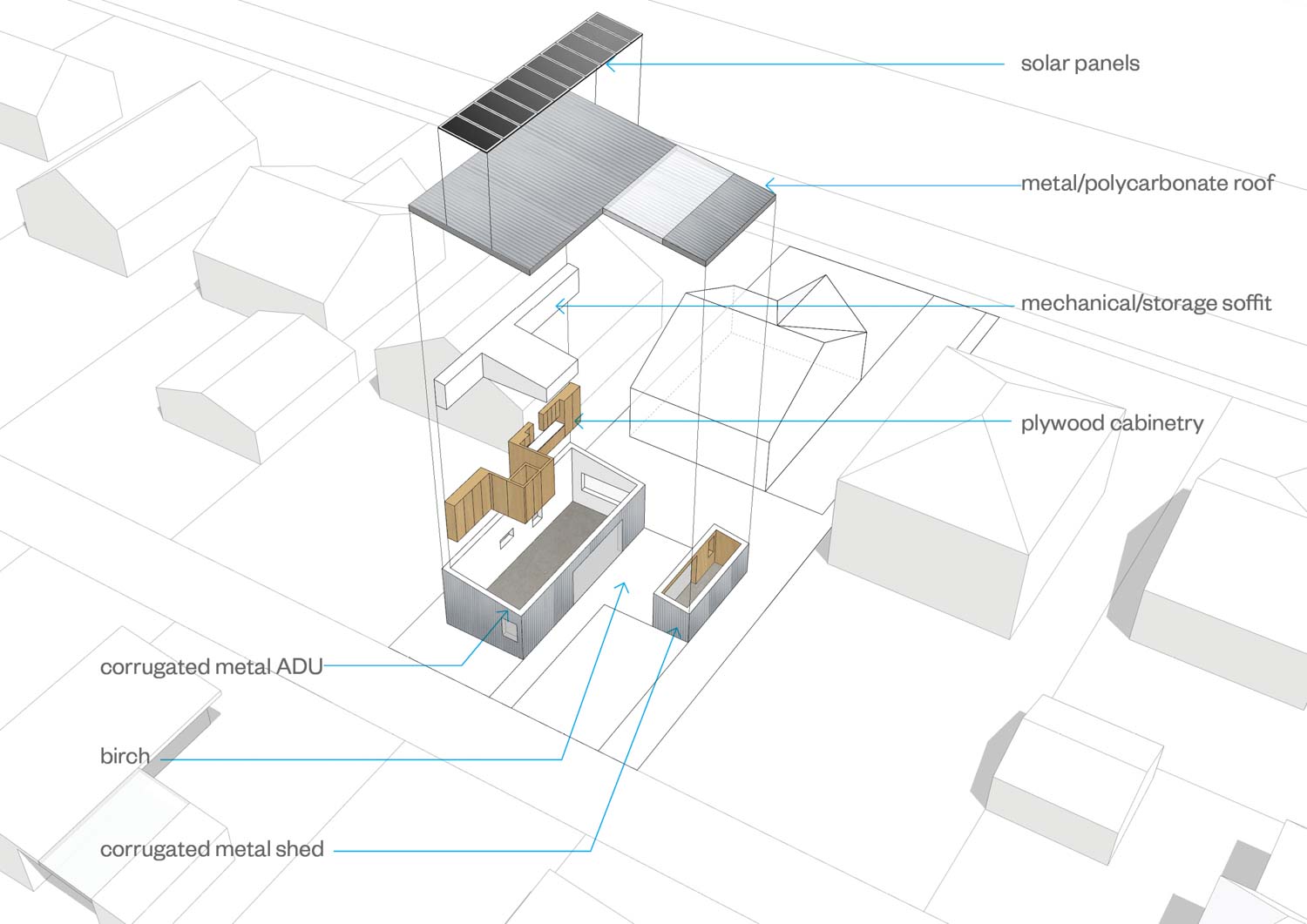

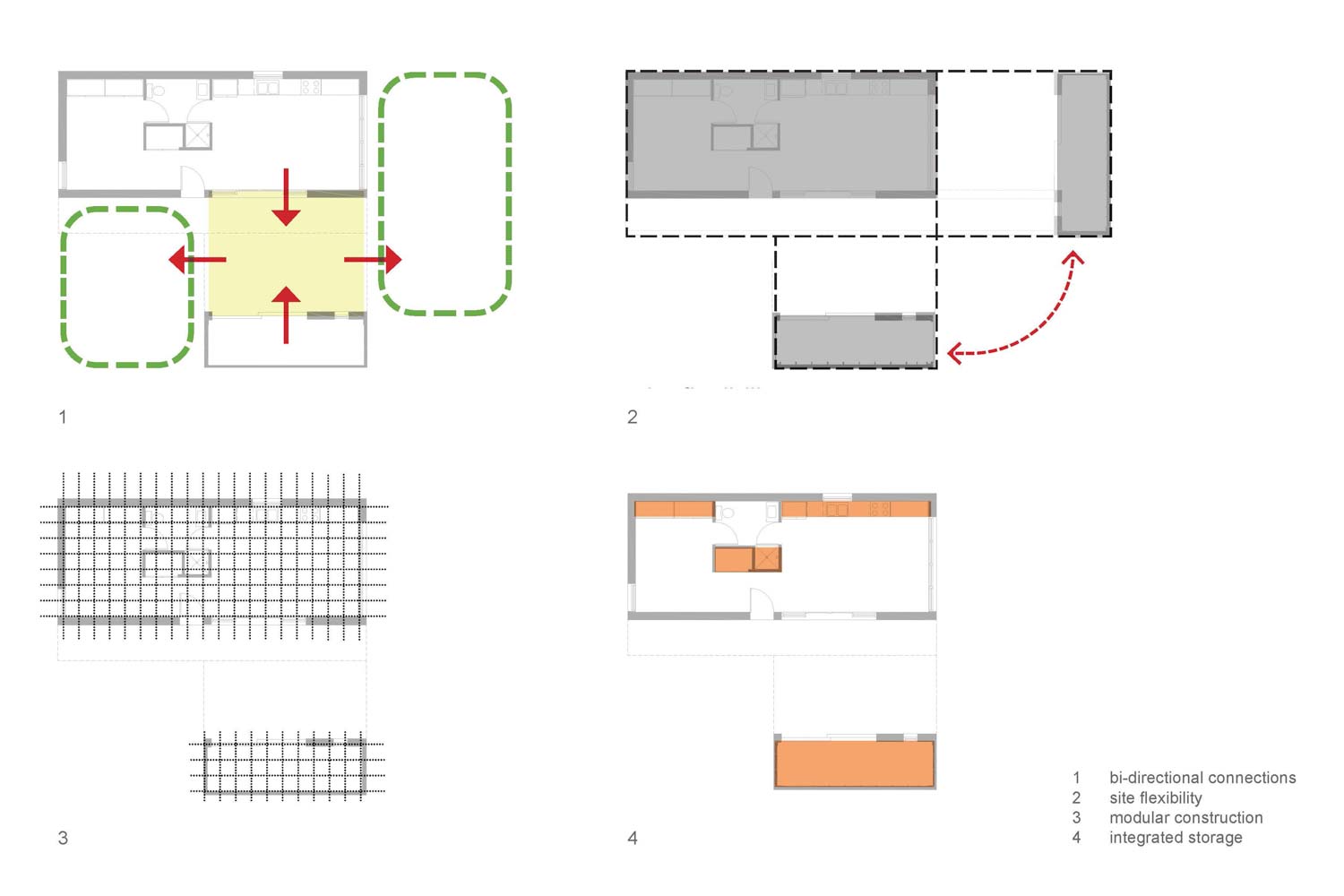

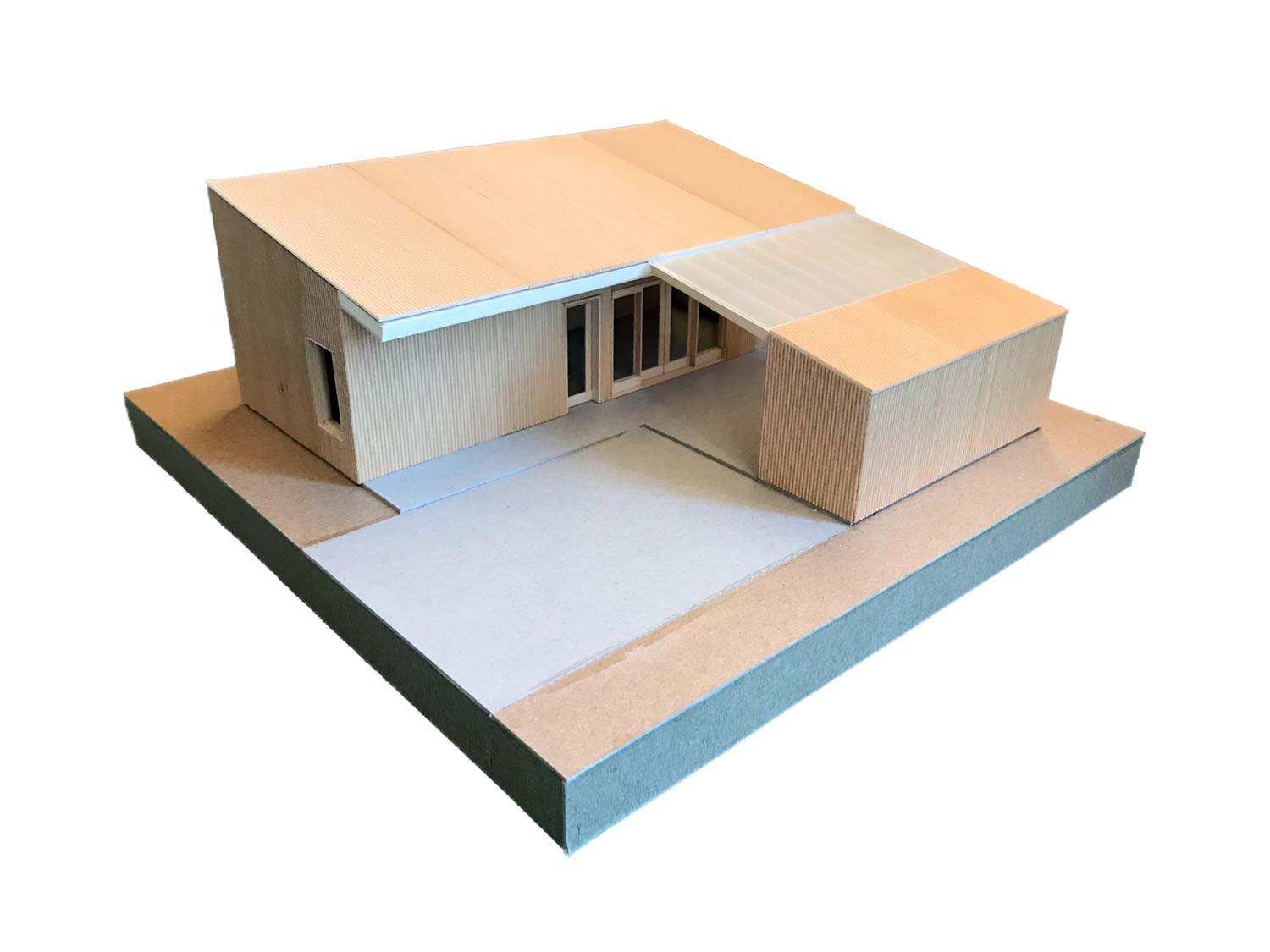

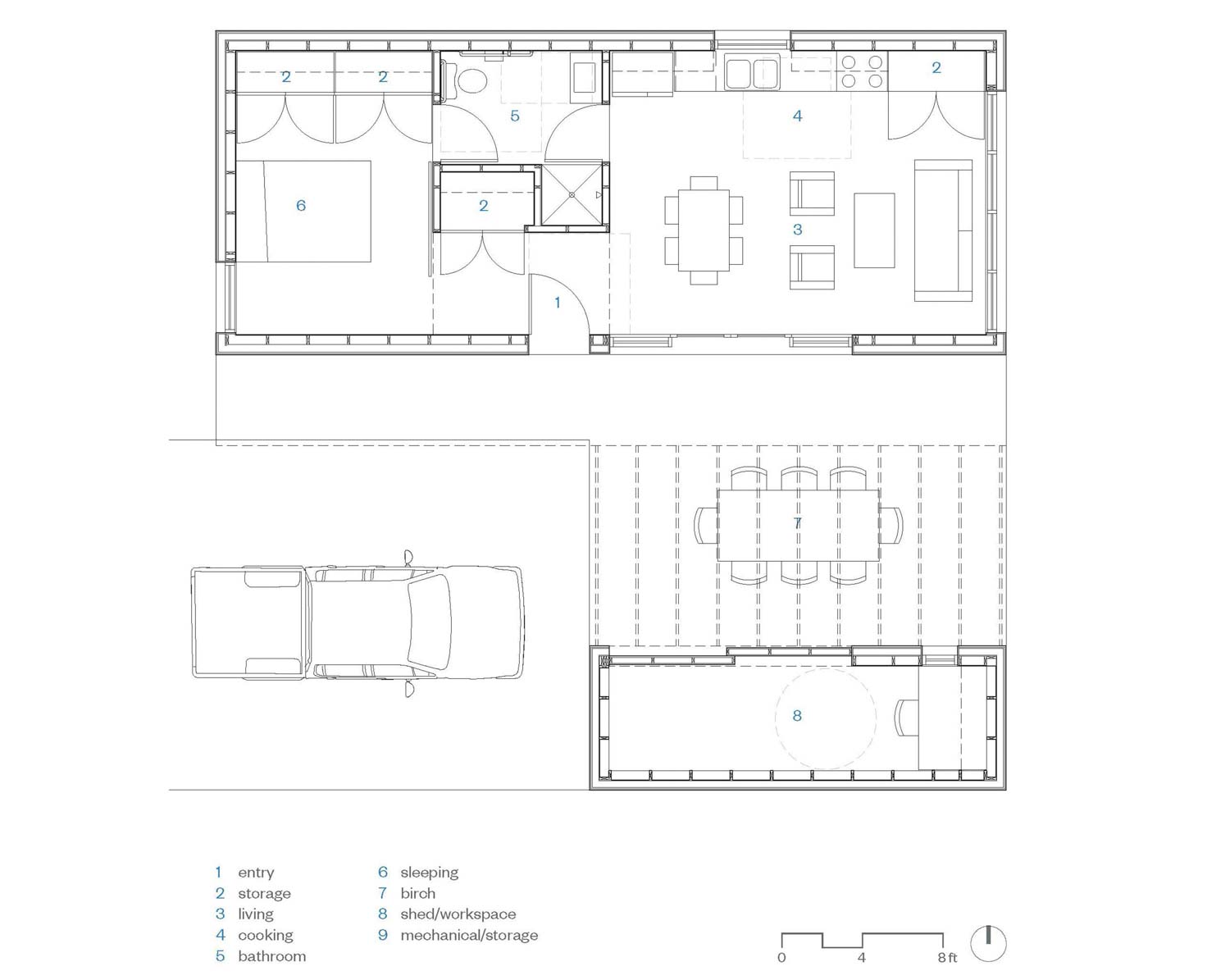

WBA: The Birch ADU is more than just a small home — it’s a kit-of-parts that allows flexibility and adaptation across sites. The most unique piece is what we call the “birch” — short for BI-directional poRCH. This covered outdoor space connects the interior to the exterior and acts as a social hub, workspace, or relaxation area. It extends the sense of home beyond the walls and encourages community in unexpected ways.

3. How did sustainability and affordability shape your material and design choices?

WBA: From the start, we wanted this to be a realistic and affordable prototype. That meant simplifying the structure and working with common, durable materials. The modular approach keeps construction efficient, and the compact footprint means lower utility demands. We also emphasized passive design strategies — orientation, shading, and cross-ventilation — to reduce the energy load without requiring expensive tech.

4. What was the biggest design challenge, and how did you solve it?

WBA: The biggest challenge was designing something that feels custom and contextually rich, but that could also be repeated affordably across many different sites. That’s where the modular “kit-of-parts” became essential — it allows for flexibility in layout and orientation, but still gives each unit a distinct presence. It’s a strategy that adapts rather than imposes.

5. How does the Birch ADU contribute to the broader conversation around urban density and housing?

WBA: ADUs are one of the most immediate tools we have to increase housing supply within existing neighborhoods. What’s powerful about the Birch ADU is that it doesn’t require demolition or major disruption — it adds gently. It supports multigenerational living, renters, or aging-in-place. We see it as a way to offer missing middle housing in cities that need it, without erasing neighborhood identity.

6. What’s next for the Birch ADU — or this type of small-scale urban housing?

WBA: We’re continuing to explore how prototypes like Birch can be used in real-world development — whether it’s through city partnerships, policy change, or prefab construction. The interest is definitely growing. More cities are recognizing that backyard housing isn’t just a trend — it’s part of the solution.

Want to learn more or explore similar urban infill strategies? Visit Woofter Bolch Architecture for ongoing research and design projects at the intersection of community, sustainability, and architecture.