Backyard House: A Clever Multi-Generational Living Solution in Brunswick East by Tan Architecture

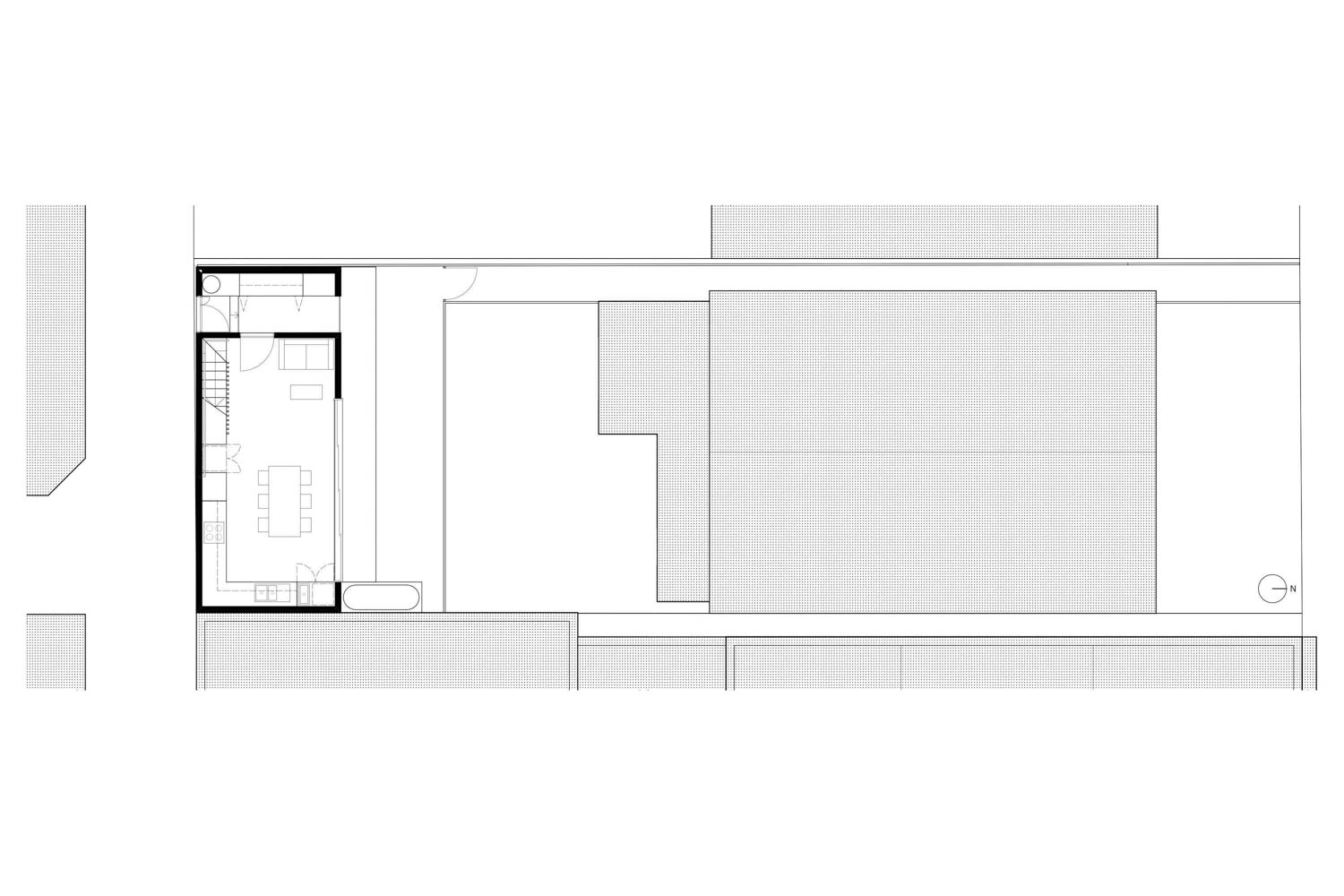

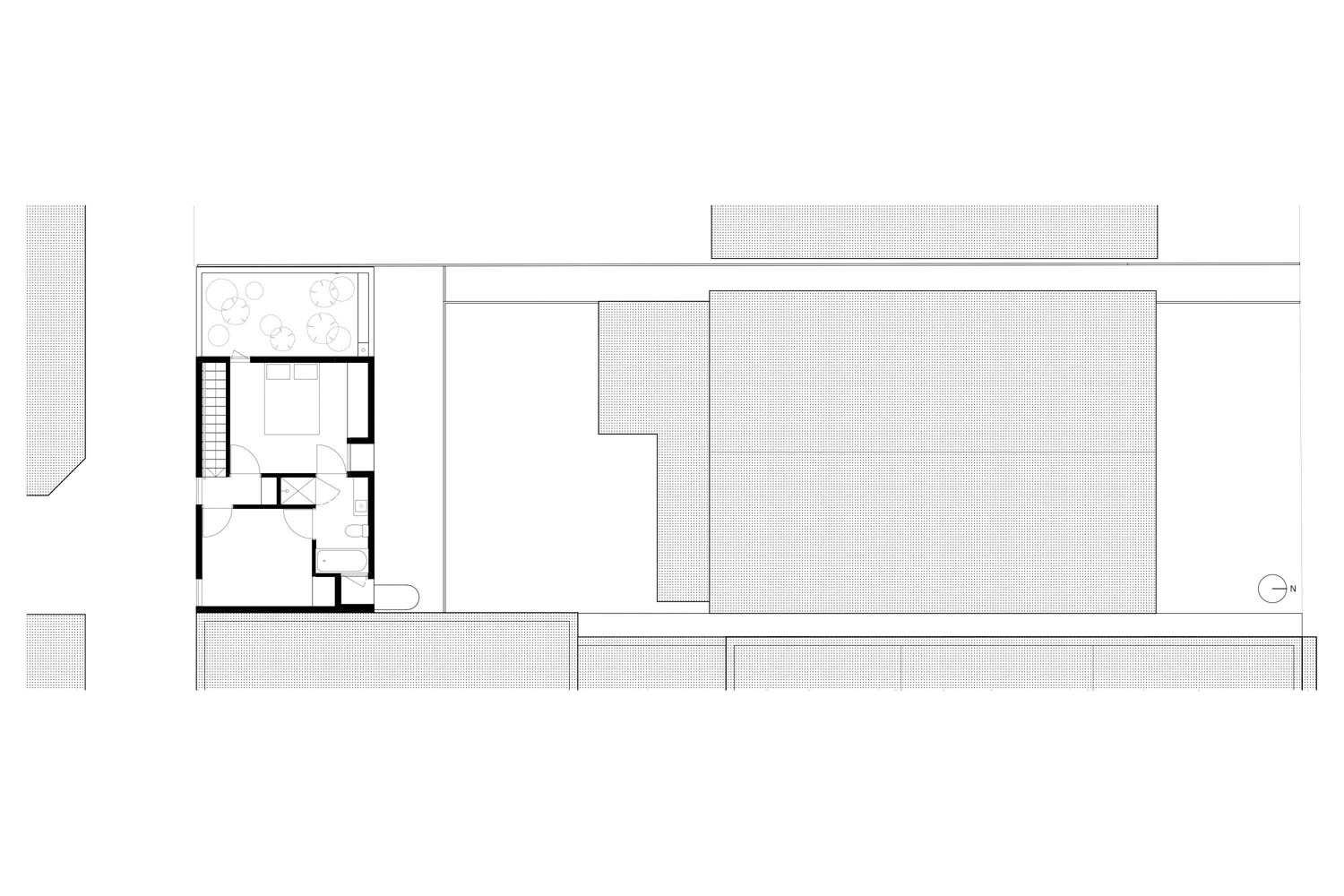

Located in Brunswick East, Melbourne, the Backyard House by Tan Architecture showcases an efficient design that accommodates multi-generational living in a small space. This project transforms a backyard into a functional two-story, 69sqm home for the client’s parents, allowing three generations to live together while maintaining privacy. The design cleverly addresses challenges like privacy, solar access, and ventilation within a compact urban setting. Surrounded by a mix of single-storey homes and newer developments, the Backyard House offers a practical approach to increasing housing diversity in Melbourne.

Published with bowerbird, photography by Adam O’Sullivan

Can you describe the Brunswick East context to our international audience? What’s the housing stock like of the local streets and what kind of developments normally occur?

Brunswick East is considered an ‘inner suburb’ of Melbourne, about 6km north of the CBD. Housing on the local street consists predominantly of single-storey detached dwellings, with some newer double-storey developments. Multi-storey apartment buildings can be found along and around the commercial or ‘growth’ zones along main roads going through the suburb.

You mention that the home is for the client’s parents, and allows 3 generations to stay in close proximity, whilst maintaining privacy. Can you describe anything further about the client’s objectives? The site’s features and how they utilised the full block for their family?

The most concise answer I can probably give is that this family wanted to live close to each other, and looked for a way to make that a physical reality. Rather than extending the existing house, the client opted to build a small separate dwelling at the rear which I think was a smart move, not just in terms of meeting the functional objectives, but also in providing future flexibility. I’m happy with the way we apportioned the back yard to provide two private gardens, and of course enough of a footprint for a comfortable self-contained dwelling.

The two storey house within 69sqm is impressive, and a great utilisation of space in the backyard. Were there any challenges with the setbacks and dealing with privacy, solar access and achieving cross ventilation in such tight parameters?

Yes, the dense programme on a small subdivision certainly brought some challenges. For me, the form and layout of a building are influenced by key considerations such as the ones you mentioned, and part of my process is to get a more instinctive understanding of the factors at play through drawing and experimentation. The aim is always to come up with something that addresses all of the functional and regulatory requirements in a way that is both practical and delightful.

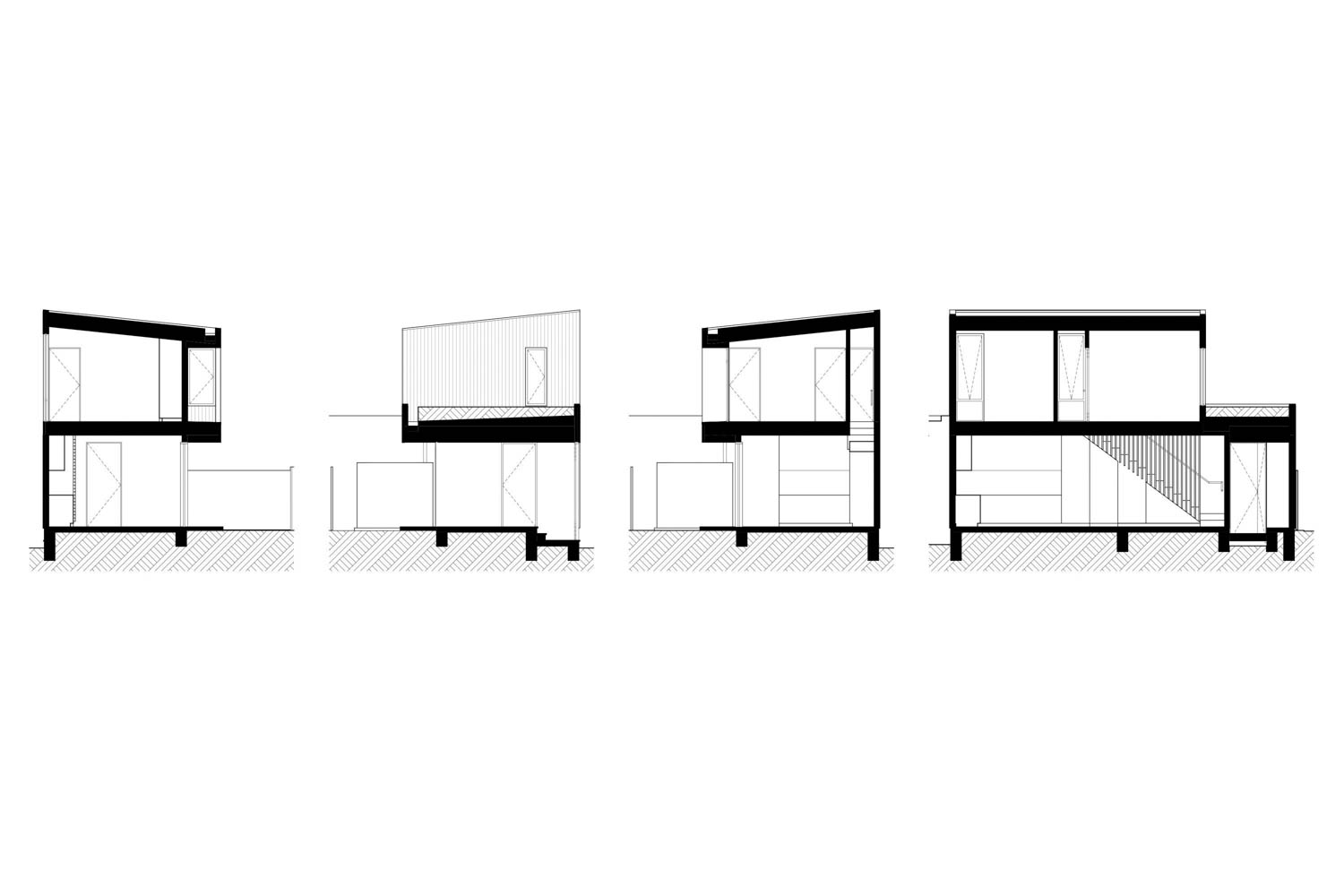

Can you elaborate on the design considerations that led to the sloping roof and how it helps in minimizing the visual bulk from the street and the existing house?

The upper storey of the new house was going to be visible from the kitchen and back yard of the existing house, so I wanted to reduce the visual impact of the new house without making the upper storey spaces feel too low. To achieve this, I dropped the ‘front’ edge of the upper level (i.e. the northern edge facing the old house) to 2.2m internally and raked the ceiling up to a generous 2.7m at the rear. The robes were placed on the low side of the bedroom ceiling. As a result, the house looks smaller from the north than it feels on the inside.

The upper level of the new house was also set back from the west boundary to avoid overlooking and minimise overshadowing of the neighbour’s back yard. Along with the sloping roof, this makes the new house almost invisible from the street. I like how this adds a sense of surprise and quietness to the house.

How did you integrate the north-facing main living area and terrazzo flooring to optimize thermal mass and reduce heating needs during cooler months?

The upper floor cantilevers over the living area downstairs by just under a meter. This extends the useable area upstairs while acting as an eave over the glazed sliding door below, protecting the opening from rain and reducing heat gain in summer. In winter, sunlight enters the space on a lower angle from the north to passively heat the space. In short, this means that radiant heat from the sun is absorbed largely by objects

in the space, including the terrazzo flooring, which has high thermal capacity. This absorbed heat is gradually released back into the space, increasing comfort without sudden temperature changes, and with minimal active heating.

Could you describe the process of collaborating with the owner’s family, especially having a skilled carpenter, and how this influenced the selection of fittings, finishes, and custom details like the joinery handles?

My role was to design and document the house for planning and building approval, and to produce a set of drawings suitable for costing and construction by the owners, so much of the final selection of fittings and finishes was left to the owners.

I really enjoyed watching the family build and fit the house, though. I like it when the final product is informed by the personality of people I work with, and I think this house is a delightful example of that. I’m really proud and happy with what the family has achieved.

How do you see this project as a good model for future designs for multigenerational living spaces?

One of the successes of this project was having both client and council take the opportunity to insert a small dwelling of high quality into an area that, like much of Melbourne outside the CBD, has historically adopted a low-rise detached housing typology. This was what allowed the client’s family to realise their vision of living close together.

I think it’s important to recognise the local council’s contribution to the realisation of this project by adopting policies that encourage densification and reduced dependance on cars. For example, council waived the requirement for on-site car parking, which would otherwise have left this project (and by extension, any similar projects in the future) dead in the water.

So yes, I do see this as a good model for multigenerational living using a site layout that is reasonably common in Melbourne, as well as a good way to increase housing diversity around the city. However, this can only happen with the support of local residents and councils. I’d love to see our somewhat archaic ‘minimum car parking’ laws rewritten so that on-site car parking is no longer seen as some kind of basic necessity, and I’d love to see a general shift towards a mindset of ‘smaller and better’ rather than the sadly familiar suburban sprawl, and in some ways, the sometimes fevered protection of the single-storey status quo in many of Melbourne’s inner suburbs.